Pěkné i když smutné čtení .

The Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) Part 3

Categories: Years of war and revolution , Třicetiletá válka

Battle of White Mountain

The news from the Czech front was grim. Hungry and unpaid mercenaries refused to fight and retreated even under light pressure. Mansfeld and Hohenlohe accused each other of incompetence and gradually cleared positions up to the line Třeboň - Zábor - Písek. The enemy reached Beroun, Karlštejn, captured Hluboka and came in sight of Prague.

The insurrection reached its climax, but militarily it was doomed. The commanders quarreled, the soldiers were unfit, the treasury was empty. The Directory called in Christian of Anhalt to help. But he was a politician, a civilian, and knew little of warfare. He did not stop the crisis and led the army in a demoralized state to White Mountain.

General Buquony, meanwhile, conquered southern Bohemia (He made Rožmberk his residence. Ferdinand II then gave it to him and the castle remained in the possession of this family until 1945). Ferdinand's diplomats did not lag behind either.

A great victory was still experienced by the Moravian troops on the fifth of August at Věstonice, when they defeated General Dempierre head on.

We are waiting for a miracle

The Estates expected a miracle with the ascension of Frederick of Flanders to the Bohemian throne. They were looking forward to the replenishment of the state treasury. His authority would surely induce the Protestant princes of the Empire to support their uprising. And most importantly, his father-in-law, King James I of England, would support him politically, militarily and financially. But the expectation was not fulfilled. James I distanced himself completely. The Protestant princes had become aware of the situation and did not want to get involved. And the money? Frederick didn't have that much to fill his coffers. At the beginning of the year he was informed that the war had already cost 3,800,000 guilders and only half had been paid so far. He was shocked. A battle was about to break out on the border. It was necessary to rearm.

For a while the Czechs hoped that the situation had improved significantly. Duke Gabor Bethlen of Transylvania entered the war. He captured many Slovak towns, negotiated with the rebels, and even helped Thurn and Hohenloh in the siege of Vienna. He also won the Hungarian Estates to his side. For a while, the rebels seemed to have gained the upper hand. But Bethlen was playing a double game. At the same time he was arguing with Ferdinand II. He demanded an unheard-of 400,000 gold pieces from Frederick of Flanders. When he did not get it, he withdrew with his army.

On the other hand, Ferdinand II won the Saxon Elector (occupying Silesia and Lusatia) to his side. Lusatia was then acquired for a reward), troops from his Spanish relatives, and Maximilian of Bavaria, and the Protestant Union promised not to interfere in the conflict.

The circle has come full circle...

Move it, move it, move it.

The imperial offensive against the Bohemian Estates Revolt began in the summer of 1620. The battlefield was southern Bohemia. The imperial troops pushed the enemy from Tabor through Orlík, Rožmitál, Rokycany and Beroun to the capital. The Estates zigzagged and dodged. For four months this strange war was waged, with massive forces manoeuvring without any real fighting apart from skirmishes. The Estates troops were always positioned to prevent the advance on Prague.

In Prague, it is blissful

In 1620, a few weeks before the fateful battle, a folk festival was held in the Hvězda game preserve, where Fridrich Faltský climbed trees to entertain the court. The fact that the king danced with country girls without scruples is testimony to the looseness of the new mores and the free-spirited gap with the contemporary Bohemian environment. In the evening, a great fireworks display was held in front of the summer palace.

The Battle of White Mountain

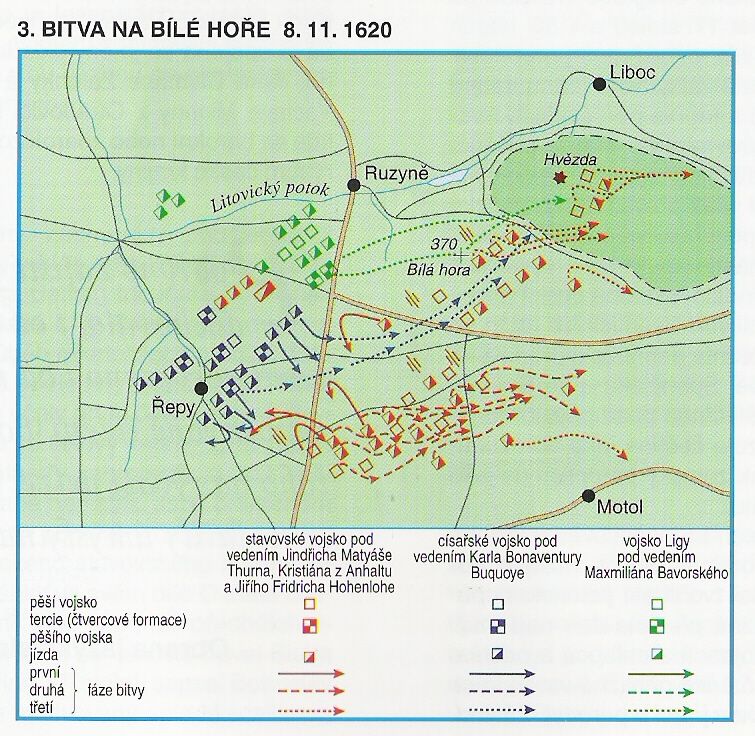

On 6 November 1620, the Estates' army rushed from Rakovník to Prague. After lengthy manoeuvring, tactics and minor skirmishes, the moment of collision of the two armies was approaching. Winter was approaching and the Estates army, pursued by the combined army of the Emperor and the League, was advancing into the heart of the Bohemian kingdom.

From Sunday morning, 8 November 1620, the Estates army had been forming, digging in and fortifying itself on White Mountain. For the defenders, this was the ideal place. The commander-in-chief of the Bohemian troops, Prince Anhalt, was himself enjoying himself. All you had to do was dig in and wait. The enemy was first forced to climb a rather steep hill. Such a slow attack could be overcome by a screen of fire.

However, ... the enemy's army swept across the plain without the state troops being able to put up much resistance. Over twenty thousand defenders scattered, and the others who saw them quickly retreated.

The officers who returned from their night march through Prague before dawn did not have time to take command. In the ensuing turmoil, the soldiers half listened or did not hear them. The troops were struggling on their own. Failure was crowned by the Hungarian cavalry, which was turned to flight by the Polish Cossacks.  There were rare exceptions. Only two, in fact. Twenty-one-year-old son of the commander-in-chief, Prince Anhalt, tried to save the day. At the head of the royal cavalry, he charged against the Spanish odds. He led the light cavalry against the heavy. He almost succeeded in breaking the battle line. Unfortunately, he needed help and it couldn't come. A heroic act turned into a trap. His father, seeing his son hit by a bullet (he was then taken prisoner), abandoned his position and, together with the generals, left the army at the mercy of the enemy. At the same moments the Moravian regiment of Šlik was fighting on the left flank. It was composed of German mercenaries, whom the Moravians had paid. They were the only ones who fought back fiercely. Their situation was hopeless. Pressed against the wall of the game-preserve, they struggled for their bare lives. They paid with heavy losses.

There were rare exceptions. Only two, in fact. Twenty-one-year-old son of the commander-in-chief, Prince Anhalt, tried to save the day. At the head of the royal cavalry, he charged against the Spanish odds. He led the light cavalry against the heavy. He almost succeeded in breaking the battle line. Unfortunately, he needed help and it couldn't come. A heroic act turned into a trap. His father, seeing his son hit by a bullet (he was then taken prisoner), abandoned his position and, together with the generals, left the army at the mercy of the enemy. At the same moments the Moravian regiment of Šlik was fighting on the left flank. It was composed of German mercenaries, whom the Moravians had paid. They were the only ones who fought back fiercely. Their situation was hopeless. Pressed against the wall of the game-preserve, they struggled for their bare lives. They paid with heavy losses.

The battle was short and ignominious. Not unfortunate! The commanders were optimistic about the situation. They thought the enemy would not make a decisive retreat. The position of the Estates troops was advantageous. If something went wrong, there was still the possibility of retreating behind the walls and defending the city with the help of the militia. Even King Frederick himself did not consider his participation in the battle important. On Sunday 8 November 1620, he hosted a celebratory lunch for Messrs Weston and Conway at Prague Castle. They were envoys of his father-in-law, King James I of England and Scotland.

Whose bell is ringing?

Suddenly, the sound of trumpets and drums is heard beneath the White Mountain. The imperial assault was launched.

As the king makes his way to Strahov Gate after the banquet, he sees only the desperate flight of his troops, including Christian of Anhalt, Henry Matthias Thurn and George Frederick Hohenlohe. No one pursued them. Both the soldiers and the commanders fled.

Nicholas Bell's Relation (1625), in describing the losses, states that the people "...most around the preserve of the Star, yea, even in it, are slain ...". .... "What soldiers fled from the battle, they thought to keep their throats in the preserve of the Star, but the imperial and Bavarian people would not hear them, but killed them there, on the work ... ...to eat them alive," and this applied especially to the more prominent persons.

The king immediately leaves to pack only the bare necessities and, together with his wife Elizabeth Stuart

, hastily leaves Prague Castle. He reigned for only a year and four months and is therefore also nicknamed the Winter King."Frederick did not understand the environment he wanted to be a good king," says historian Jaroslav Čechura. "Even the sympathetic traits of his character - immediacy, warmth, boyishness, sportsmanship and a penchant for dancing - did not change that. His spontaneity seemed to the Prague environment as something unsuitable, unworthy of a king."

The evening after...

Towards evening, hysteria broke out in Prague. No one knew what was happening or what was going to happen. The townspeople were holed up in their houses or running out of town. The gates were jammed with carriages. Mercenaries demanding mercenary pay. The most important thing was bare existence. Generals, leaders of the Estates and the King were fleeing.

Did it have to be like that?

Prague was not conquered, the army was not decimated. Those fleeing correctly headed for the walls of Prague. There were many men in arms in Bohemia and Moravia. The mercenaries could pay. In Prague, there were the means to do so.

The Battle of White Mountain was not a total defeat.

Why didn't it happen?

There was no one capable (General Thurn's young son tried, but he didn't have the authority) to turn things around.

Days later...

Prague was surrendered to the enemy.

Ferdinand II hadn't even counted on it. The commander-in-chief Duke Maximilian preferred not to let his troops inside the city at first. But then there was looting. When he left the town after a fortnight, he was said to have taken 1,500 wagons of personal loot to Bavaria. Soldiers from both opposing sides looted as well as the rabble.

The people of Prague watched as those responsible for this situation fled, leaving them in the midst of helplessness, despair and uncertainty. The king, while fleeing, did not even take care of the crown jewels of St. Wenceslas, which were in the hands of the victors.

Charles the Elder of Žerotín

Charles the Elder of Žerotín was a leading Moravian nobleman, politician, writer and representative of Moravian regional patriotism.

Charles the Elder of Žerotín was a leading Moravian nobleman, politician, writer and representative of Moravian regional patriotism.

He was brought up in the Czech Brethren faith. He became the secular head of the Unity of Brethren in Moravia. He studied law and theology, and was fluent in Latin, Italian, French and German. He travelled almost all over Europe. He supported Jan Amos Comenius, whom he commissioned to write a Gerontian genealogy and also financed his studies in the German lands.

He became actively involved in politics only in 1607, when he sided with Matthias of Habsburg in the dispute between Rudolf II and Matthias. He held the view that religion and politics were incompatible and advocated religious tolerance. Against joining the rebellion of the Estates he said: 'The Bohemians are trying to become famous by destroying their country. Their defeats will be the beginning of ours, but the blame will be entirely theirs. On 13 December 1618, he then persuaded the majority of the Moravian Estates to neutrality and negotiation. However, he could no longer prevent the coup. After the victory of the opposition in Moravia, Charles Sr. was kept under house arrest for some time. After the Battle of White Mountain, he was one of the few non-Catholics offered to stay on his estate. During this time he tried (especially financially) to help the victims of the recatholization of Moravia and Bohemia. He died in Přerov.

The article is included in categories: